|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ORDER A COPY of An Honorable Run by Matt McCue

| An Honorable Run (an excerpt)

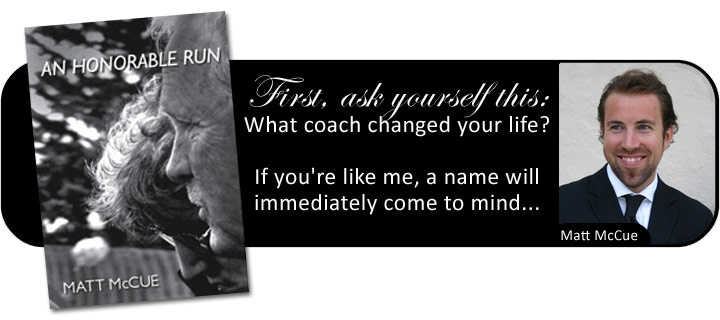

An unheralded 9:30 two-miler from a small Iowa high school walks on the University of Colorado cross country team. Living his dream, he finds himself rooming with his heroes, Jorge, Ed, and Dathan, and being led by the legend, Mark Wetmore, or simply “Wetmore” as the enigmatic coach is known on the team. However, competing for Colorado is more challenging than the walk on had ever anticipated. The running, he finds, is the easy part. He works as hard as he can just to keep his place on the team.

To help pull him through the rough patches, he remembers the advice of his high school coach, Coach Brown. He is the wise 58-year-old who the runner brashly left behind when he headed west with aspirations of being bigger than whatever small-town Iowa could offer.

In an exclusive excerpt from his new book An Honorable Run, written in journal format, Matt McCue recounts his experiences that took him on wild training runs up mountains and through blizzards as well as provided an opportunity for quiet reflection about the coach who changed his life.

| Mount Elbert: The most pleasurable $4.99 prime rib dinner of my life: July 2002

After one daybreak run during the summer between my freshman and sophomore years, a couple of teammates and I were hanging around at Potts track when Wetmore showed up and caught our attention by casually throwing out an idea: run up Mount Elbert, the tallest mountain in Colorado and the second highest in the contiguous United States. Wetmore, who would lead the trip, emphasized that the proposed run was completely voluntary. My fellow walk-on, and good friend, Travis, and I figured that he would have another reason to keep us on the team if we nearly killed ourselves by scaling the peak. We were in.

|

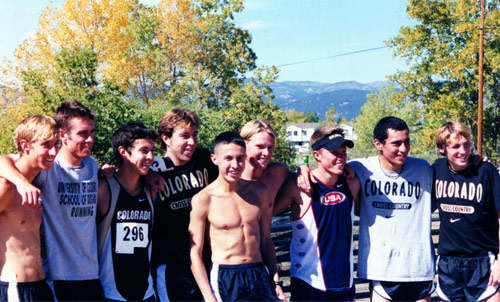

| Members of the 2001 University of Colorado cross country team, including Ed Torres (third

from the left), McCue to his left, Jorge Torres (shirtless), and Dathan Ritzenhein (far right).

Photo submitted

|

On a Friday afternoon in late July, ten men, two women, and Wetmore endured the three-hour mountainous drive from Boulder to Mount Elbert, located ten miles south of Leadville in the San Isabel National Forest. A potholed dirt road welcomed us, once we had left the highway, and led us to the trailhead. In front of us, Mount Elbert seemed to bulge outward from the ground like Buddha’s belly, giving it a wide girth that disguised its unparalleled height.

We set up camp in the middle of an evergreen forest between the trailhead and a rushing stream. One of my teammates owned a four-person pop-up trailer that we had hauled up from Boulder. That’s where Jorge and Ed, Dathan, and I, along with a few others—eight people in all—planned to sleep. Wetmore had brought his tent and pitched it next to his Subaru.

That night, we drove into Leadville and ate dinner at a Mexican restaurant. As we inhaled baskets of chips and salsa, Mark outlined our ascent. He planned to split us into small groups based on our fitness level, staggering our start times, with the slower guys leaving first, followed by the faster groups, minutes later. Theoretically, everyone would arrive on top within a ten-minute window. Fearful of injuries, Wetmore warned us not to run too hard. Run too hard? That was typically Wetmore. He knew that merely walking up Mount Elbert would leave us wheezing.

That night, our group gathered around the campsite’s wooden picnic table. Forcing fluids down our gullets and snacking on chocolate animal crackers dipped in peanut butter, we told rowdy stories, trying to outdo each other. An electric lantern provided a flicker of light as Wetmore shared his experiences of coaching his former New Jersey high school and club runners. Years ago, he had driven some of them out to Colorado for a summer running trip. In the spirit of gamesmanship, they had participated in “heart rate contests”, where they had dashed up the peaks surrounding us to see who could push their pulse higher than the others. One year, the winner had apparently pressed so hard, he had begun coughing up “black stuff”.

Thanks, Mark, I thought, that’s exactly what we wanted to hear hours before our test.

As the night had drawn on, Wetmore’s tangents gave way to grand stories where he laughed at the punchlines alongside us. He seemed to let his guard down and the coach-athlete barrier, that has always been so apparent between us, vanished. In a rare moment, Wetmore talked to us the way an old friend would have.

At seven sharp the next morning, everyone met at the trailhead. The anticipation of the day ahead seemed to beg for less enthusiasm and more solemnity. The weather couldn’t have been more idyllic. All we could see was the deep blue ether of Colorado egging us on to “Have a day!” as Coach Brown used to cheer enthusiastically before big races.

Minutes after Travis’s group had set forth, my three-person pack clicked our watches. Mere steps later, the rocky trail turned steep, twisting through the tree line and taunting us with the challenge that lay ahead. The four-and-a-half-mile trek boasted an alarming incline of nearly 1,000 feet per mile and very little in the way of switchbacks.

When I caught up with Travis above the tree line, I found him laboring like me. Our heart rates were off the charts and still climbing: thump!thump!thump!thump!thump! Like everyone else, including Wetmore who was slogging up behind us, we barely moved faster than a walk in the final half-mile, our efforts reduced to almost nothing by the thin air.

“Can—you—HUH!—believe—these—HUH!—views?” asked Travis, staring out into the expanse of snow-capped peaks in every direction.

My eyes remained locked on the talus-lined trail. “I—HUH!—don’t care—I—HUH!—just want to—get—HUH!—to the—top!” I replied in pants, after coming across another false peak.

After seventy-five minutes—16-minute miles!—we had reached the final 100 meters, a flat bed of rock disks. The smooth plane was the best welcome mat I could ever have hoped to find. Our group stood on the highest point in the state and shared sips from a water bottle someone had prudently snatched up and carried at the last minute. As the marshmallow clouds blew in, we started down. The urgency was gone. The descent would be relatively lazy and easy.

Fifty-eight minutes later, we returned to our campsite where we finished the morning with a painfully cold, waist-deep ice bath in the glacial stream. That night, we went to a restaurant that advertised an early-bird special for only $4.99. I greedily consumed the most pleasurable prime rib, baked potato, and chocolate cake dinner of my life. Satiated, and ready for bed, we returned to our campsite. By eight, it was pitch black and silent outdoors.

The following morning, Travis and I stretched on the shore of neighboring Turquoise Lake after a ten-miler around the water’s edge. Our shoes and socks carelessly tossed to the side, we waited for Jorge, Dathan, and Ed to finish their twelve miles before returning to Boulder. Despite his grizzly summit push, Wetmore had chalked up his daily run. Travis and I found ourselves alone with him, giving us an opening to ask about the budget-cut rumors we had heard the week before from our teammates. We had quickly caught on that we would be among the first to go, if Wetmore thinned the roster. The last week of uncertainty had been painful, the thought of leaving the Buffaloes inconceivable.

With enough sense to raise the matter right after we had run up the tallest mountain around, I started, “Mark, we’ve heard this budget-cut rumor,” and Travis finished with, “Should it be something for us to worry about?”

Wetmore paused, looked down at his clasped hands, then crossed his arms and stared at the awe-inspiring views in every direction, weighing his thoughts. He looked off in the distance when he told us how much he valued our loyalty, strong work ethic, and commitment. The coach conceded that while he would have to be careful with the budget, he would find a way to keep us on the team.

Thank God, I exhaled. My anxiety finally subsided with Wetmore’s reassurance.

Remember when you were at your best: August 2002/March 2001

My biggest concern at Colorado had always been making the team, not staying on it. I often wondered: what more can I do? I was ticking off the miles, lifting weights, stretching, dipping into ice baths, eating right, and sleeping soundly. By virtue of committing so much time to my sport, I had little to no social life. Any extra energy I had was invested toward earning my degree—the reason I was in college! But, to me, racing fast was the priority. I was doing all I could to improve, and the reality was that I had risen only far enough to ensure I would not be cut. Afraid that Wetmore might perceive me as weak-willed, I refrained from confiding in him.

|

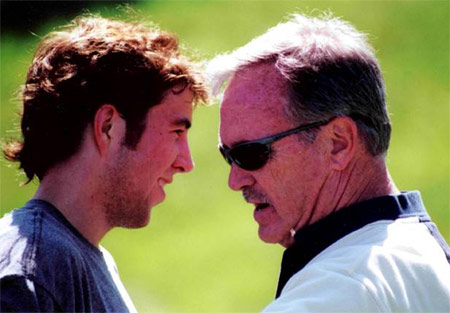

| McCue's high school mentor, Coach Brown, and McCue, finally seeing eye to eye

Photo submitted

|

But, after Mount Elbert, I decided I needed help, if I was going to succeed during my sophomore year. I wrestled with the thought of sharing my angst with Coach Brown, but after the way I had brazenly left him for the promise of Colorado, my pride wouldn’t allow me to go crawling back to seek his advice.

However, a few days before cross country season officially kicked off, I escaped for a trail run on my own. The solitude offered me the chance to reflect on one of Brown’s favorite truisms: “Remember when you were at your best and be there again.” Alone in the woods, I let my mind wander back to Iowa and my senior year of high school, a Saturday morning in March 2001...

A month after Coach Brown had declared, “I’ll let you run wild, but you have to run wild on my terms,” he and I journeyed through our final track season together. In a surprising twist, our Saturday-morning workouts, where I ran and he rode his bike alongside, had become a welcome ritual for both of us.

Arriving at Regina a few minutes before nine, I pulled my fleece headband over my ball cap. A punctual man, Coach drove into the vacant parking lot a minute later and pulled his blue Schwinn from the back of his jeep.

“Are we ready?” he asked amid the sheets of rain, the bike already dripping. His gray- blue eyes squinted against the drops, tiny lines stretching themselves out across his temples. Coach Brown wore a baby-blue rain slicker and matching waterproof pants. He looked like Papa Smurf.

“Let’s go,” I replied.

The streets were slick and black, empty of traffic. The aroma of bacon leaked from the houses, seducing the inhabitants into hibernating during the seemingly endless Iowa winter.

We separated when we hit the sidewalk, less than 100 meters into the twelve-mile run. I moved to the front; Coach Brown trailed a few steps behind. Neither of us uttered a word. With a companion to share the road, silence can be comforting.

We left the city and traveled toward the Iowa countryside. The concrete road ran in front of us like a river of gray. Spray pelted our faces when a passing truck bumped over a pothole. We were the only two people on the road, lost in a sea of red barns, wheat-colored fields, and rows of leafless trees waving their chocolate-hued branches.

Many times, we tried to talk, but for the majority of the journey, we yo-yoed. Either Coach Brown would fly down a hill and wait for me to catch up or I’d pull away on an uphill and he would try to rein me in. Our last climb was no exception; the only difference being that by then, it was snowing.

I never admitted it to him, but the way Coach had shared the road and pedaled next to me through blowing flakes made me feel like I was invincible. Wanting to feel like that again, I held onto the memory during the fall and continued working hard. By spring, my confidence had returned. I would finally have the breakthrough I had been chasing.

Mother Nature, an unrelenting beast: March 2003

A breakthrough wouldn’t have been nearly as fulfilling without having to overcome a few obstacles along the way. One unexpected challenge came in late March, courtesy of Mother Nature. An abominable snowwoman, she took her aggression out on Boulder in a pre-spring blizzard that clobbered the Front Range late one night. The violent storm forced the city to close icy Canyon Road, a rare occurrence that eliminated our only connection between the Fight Club, the cabin where I lived with Jorge, Ed, and Dathan, and town.

Around eight-thirty the next morning, I woke to a dark house that felt like an ice box. The electricity lines were dead, knocked out by the snow’s weight. An hour later, my roommates and I shuffled out of bed. Outside, we saw a solid field of thigh-high snow extending from the Fight Club’s front door, engulfing the roundabout driveway and continuing down to Canyon Road 100 yards away. After dressing in every piece of winter-weather attire we owned, Dathan and I grabbed the only two shovels in the garage. Jorge and Ed settled on plastic rakes and we relentlessly dug for the next two and a half hours. Finally, sweating from the unexpected chore, Jorge pulled us together. “It looks pretty good. Now we can at least get a car out.”

|

| Coach Wetmore, on the far right, checking his watch and keeping tabs on McCue, the

second runner from the left, during a race at the Buffalo Range - Photo submitted

|

“Jorge, the road is closed,” Ed told him. “Where are we going to drive?”

He had a point.

The next logical step would have been to build a fire in the fireplace and boil a pot of hot cocoa over the open flame. But, freakishly, we had more important plans than indulging in liquid chocolate, if that’s even possible. We robotically changed into tights, long sleeves, waterproof vests, caps and gloves. On Wednesdays, we were scheduled to run fifteen percent of our weekly quota. I had recently been experimenting with 100 miles a week; that meant fifteen for me, as well as for the others. It was an aggressive workload, where we walked a fine line between injury and victory.

Since snow covered the dirt trails, we used the lifeless Canyon Road which had been partially cleared. It would have been one of the busiest roads in Boulder on a normal workday. We jogged over the wooden bridge above the creek and clicked our watches. Like Coach Brown had said whenever the Iowa weather turned inclement, “Run tough when it’s tough to run.”

We cruised down the center of the road, atop the yellow lane-dividing line. It felt rebellious and freeing. Despite the massive orange snowplows that threatened to flatten us with each pass and the police roadblock set up at the bottom of the canyon, our Wednesday run into town proceeded smoothly. After forty-five minutes, we popped into Balch Fieldhouse. Colorado’s closed campus was devoid of life, yet we all knew at least one person would be there in his office: Wetmore.

Mark also lived up Boulder Canyon, but had driven down before the police erected their roadblock. Seemingly indifferent to the weather, he penned the day’s assignments as if the sun shone and all was as usual. Almost the entire team would show up two hours later for practice, wearing the same “Snow? What snow?” attitude as Wetmore. By the time we ran to his office, we had completed half of our workout, so he waived our attendance at practice and sent us back home, knowing we’d complete our remaining seven and a half miles along the way. With vests, tights, and shoes covered in melting snow, our small group headed back into the storm. After we had convinced the police that they had to let us past their barricade because “we live in the canyon!” and “yes, we know cars aren’t allowed up the road. That’s why we’re going to run!” we started the last push.

We reached the Fight Club and continued past the ninety-five-minute mark, ultimately clocking in at two hours, about eighteen grueling miles. The extra distance convinced us that no one in the world could be working harder than we were at that moment. But we might as well have kept going, we thought, because without electricity or running water, we didn’t have much waiting for us back at the Fight Club. We did our best to improvise. That night, Jorge, Ed, Dathan, and I cooked lasagna on the grill, melted snow for drinking water, and skipped showers. As darkness fell, we covered ourselves in layers of blankets, lit a cluster of candles, and listened to the Iraq War coverage on a battery-powered radio.

|

To order your copy of An Honorable Run, CLICK HERE

A portion of the book’s proceeds will benefit the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (www.pancan.org), an organization that advances research, supports patients and creates hope for anyone affected by pancreatic cancer. More information can be found at www.anhonorablerun.com.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|