For decades, Spokane, Washington has been known as a hotbed of American distance running. From Olympic-level competitors to high school cross country dynasties, Spokane has produced a steady stream of top-shelf talent since the days of Gerry Lindgren. So strong have the boys teams, in particular, been over the years, that Spokane has earned the nickname of "American Rift Valley" in certain circles. How to explain the persistent, deep, constantly replenishing pool of talent from this one mid-sized city, tucked away in a corner of the country?

In Part 1, Dave Devine explored the relationship of tradition and landscape to the Spokane running scene. Here, he looks at the impact of the local running culture, longtime Mead coach Pat Tyson, and the tight but competitive fraternity of coaches in Spokane. Plus, he asked stats guru John Sullivan to compile a special Sully's Stats: Spokane Boys Milers and 2-Milers.

The Running Culture  At the corner of Spokane Falls Boulevard and Post Street in downtown Spokane, directly across from City Hall, sits a sinuous bronze sculpture entitled The Joy of Running Together. Dedicated in 1985, it was a gift to the city in honor of the annual Lilac Bloomsday Run. Over a hundred feet long and hugging the shaded edge of Spokane’s main riverfront park, it’s a captivating, unmistakable monument to the sport of running—a celebration of the simple ecstasy of movement. There are metallic depictions of people tall and short, young and old, long-legged and wheelchair-bound. Laughing children in the park climb over and among the figures, racing the immobile athletes, trying to imitate their poses, inheriting an intrinsic love for the act of running. At the corner of Spokane Falls Boulevard and Post Street in downtown Spokane, directly across from City Hall, sits a sinuous bronze sculpture entitled The Joy of Running Together. Dedicated in 1985, it was a gift to the city in honor of the annual Lilac Bloomsday Run. Over a hundred feet long and hugging the shaded edge of Spokane’s main riverfront park, it’s a captivating, unmistakable monument to the sport of running—a celebration of the simple ecstasy of movement. There are metallic depictions of people tall and short, young and old, long-legged and wheelchair-bound. Laughing children in the park climb over and among the figures, racing the immobile athletes, trying to imitate their poses, inheriting an intrinsic love for the act of running.

Several blocks west is the modest office of the Lilac Bloomsday Run, a converted house which is now the permanent home for a one-day event that’s become a year-round undertaking. When you walk through the front door you find an unassuming man at the race director’s desk, a familiar face to serious fans of American distance running. Don Kardong, fourth-place finisher in the 1976 Olympic marathon and noted running journalist, offers a firm handshake and admits he still has a hard time believing this is where he’s landed. Detail from The Joy of Running Together, Photo by Dave Devine

“I never thought, when I helped start this race in 1977, which 1200 people showed up for, that it would be someone’s full-time job to organize it someday.”

The Bloomsday Run has become exactly that, a yearly 12-kilometer race that attracts more than 40,000 participants. Kardong, who’s been everything from an elementary school teacher to a magazine writer, is now responsible for shepherding the event through the long months between its annual May staging. Asked to put his finger on the pulse of what makes Spokane such a vigorous exporter of running talent, he alludes to all the usual suspects: tradition, Lindgren, the landscape (Kardong moved here in 1974 because he liked the climate and the pace of life), Tracy Walters (a co-conspirator in starting the Bloomsday race in 1977, and still a loyal volunteer), and the other coaches who picked up the torch and continued the tradition. When it comes to the role of Bloomsday in the equation, he’s modest but straightforward.

“Certainly, we’re part of it. To be a distance runner in Spokane is kind of cool. It’s not nerdy.” He points to the “Fit for Bloomsday” program in the local elementary schools, which involves over 6000 kids, and the fact that almost 10,000 participants in the massive Bloomsday field are aged 18 and younger. “Usually kids who run in the high schools around here have run Bloomsday as children with their families.”

It’s a comment which echoes something Kelly Lynch, Mead’s top returner in 2007, mentioned the day before: “I’ve been running since I can remember, but it all started with Bloomsday when I was younger. I used to run it with my family.”

Lynch also says that while most top-level high schoolers don’t run the race because its May timing conflicts with the state championship progression, many are still involved as volunteers or race supporters. That level of involvement, Kardong suggests, that top-to-bottom commitment of a city to a road race, is what sets Bloomsday apart from similarly-sized events like the Peachtree 10k in Atlanta, Georgia, or the Sun Run in Vancouver, B.C.

“Sure, it started with Lindgren,” he says. “All of Washington was enthralled with his exploits. And if this were a bigger city that excitement might have tended to erode, but here people picked up the torch and carried it. Everyone realized there’s something special in Spokane.”

The Tyson Factor

Out on the back deck of Tracy Walters’ home, with a bowl of ice cream imminent and a panoramic view of the valley sprawling in the distance, the venerable mentor of Gerry Lindgren leans forward and shifts to another topic.

“I thought I was a good coach,” Walters says, “that I really knew my stuff, but Tyson went a step beyond what I’d seen.” He’s speaking of Pat Tyson, the longtime boys coach at Mead High School who steered his team to multiple national rankings in cross country and a string of list-leading times on the track. “Pat had a gift for making everyone feel important, rallying the entire community. I don’t think you see that everywhere.”

So effective was Tyson at recruiting the hallways of Mead that he came to be known as something of a pied piper among the coaching establishment. One of the young men who fell under that spell was a freshman soccer star-to-be named Dylan Hatcher.

“I went up to Tyson in the locker room in March,” Hatcher says, “before freshman track season, because I was struggling with whether to play soccer. I said to him, ‘Tyson, how good can I be?’ And Tyson looked me in the eyes, and he goes, ‘See that kid?’ and he points at Laef [Barnes], who was running 4:07, 8:58 at the time, and he goes, ‘You can be better than him.’ And I believed it with all my heart. I’m not much of an emotional guy, but I started crying. He was so direct about it, about how good I could be. I knew from that point forward I was going to be a runner.”

Tyson, reached by phone in the midst of a summer filled with running camp speaking engagements, doesn’t shy away from his characterization as a pied piper. If anything, he embraces the image.

“I knew how to build a program,” he says of his early days at Mead, “because I’d been coaching in Seattle, so I knew things were going to pop when I got to Mead. I just didn’t know how they were going to pop. I took the Spokane history and tradition and locked into the kids with my pied piper approach.”

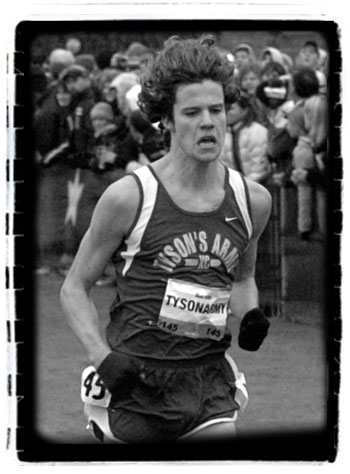

Tyson's Army "recruit" Laef Barnes - Photo by John Dye

He benefited from a school administration which supported him in showcasing the team outside the state, and an environment in Spokane that esteemed high school athletics. “We’re not a major league sports town; it’s more like a town of the ‘70s. I won’t say our runners felt equal to football and basketball, but they were pretty damn close.” Tyson says another key was the high school cross country and track coverage in the local papers. He rattles off a list of sportswriters who helped spread the word, concluding with a former writer for the Spokesman-Review. “Bob Payne was one of the best writers ever. And he did it for years. People have to know who you are, and he was able to communicate the greatness of Lindgren to the neighborhoods. And so many others after that.”

Tyson, who ran for the University of Oregon and famously roomed with Steve Prefontaine, wanted to recreate the environment of success he’d witnessed at nearby powerhouse South Eugene High while attending college in the 1970’s. At Mead, he found a program ripe for ramping to the next level.

“If you’re going to do this thing,” he says, “you might as well do it at the highest level.”

For Tyson, the echelon he sought was to be the number one boys’ cross country team in the nation. Other teams in the Greater Spokane League, content for years to compete on a certain plane, either had to ratchet up their game or be left behind. Coaches like Ferris helmer Mike Hadway, who witnessed the Tyson effect firsthand, knew they couldn’t always match the intensity, but could integrate certain things that made Mead so successful.

“I’m passionate about the sport,” Hadway says, “but Tyson is reeeeaaallly passionate. We were always at their heels, but I also learned some things from him. One thing I got from Tyson was taking the team to big meets outside the state. Pat wanted his kids to see the whole world.”

Now, with annual trips to major meets in California and Oregon, Ferris has flipped the script on Mead, winning four straight Washington 4A cross country titles and finishing third at the 2006 Nike Team Nationals.

As for Tyson, who recently left a short-lived coaching stint at the University of Kentucky in hopes of returning to his Northwest roots, he has nothing but praise and admiration for the coaches who either competed against him or followed in his wake.

“They’re all thinking outside the box now, and that’s leading them to the highest levels. Look at North Central,” he says, clearly enjoying the rise of yet another Spokane team. “They’re going to be the hot ones this year.”

A Fraternity of Competitors

Listen to Ferris coach Mike Hadway talk about his friendship with Mead coach Steve Kiesel. Listen to Kiesel talk about how he used to bring his kids from Rogers to run with Pat Tyson’s athletes at Mead. Listen to North Central cross country coach Jon Knight say that former Rogers coach Tracy Walters is like a father to him. Listen to Steve Kiesel say the same thing. Listen to Walters’ wife, Leta, refer to these men as her sons. Listen to her husband crow about their actual son, Kelly, who's the head track coach at North Central, and then marvel at the way Spokane coaches love each other and their runners. Listen to Bryce Aguilar, one of the top returners at Central Valley, speculating about the reason for his team’s recent improvement. “I don’t know...our coaches just brought a Mead and Ferris type of mentality to us. We watched what they did and started working harder.”

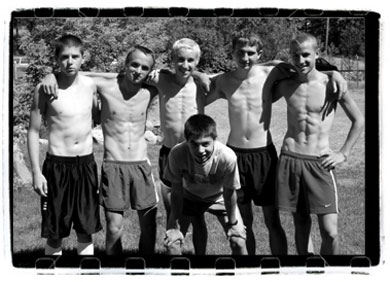

Members of the North Central team, Photo by Dave Devine Aguilar has just finished a morning distance run with several of his Central Valley teammates and is now working through a regimen of stretches. His coach, a slight bespectacled man who could easily be mistaken for one of the high schoolers, knows how far his charges have come. “When I first started helping out,” Coach James Berry says, “the varsity guys were walking on their runs. I told them, ‘The first thing you need to do is change this attitude. This is why you’re always at the bottom of the heap.’” Before last season, it had been forty years since the Bears appeared at the state cross country meet. In 2006 they were third. Success in cross country is a fairly new phenomenon at Central Valley, and the runners stretching in front of the school have all the attributes of recent converts, sporting long, basketball-style shorts as opposed to the traditional running shorts favored across town at Mead. None of which changes the fact that they’re among the teams favored to win the 4A state title this season.  A big factor in the renaissance is Berry, a second-year head coach who was a GSL runner himself at University High. Despite his callow appearance, he is completely dialed into the Spokane mystique. His grandfather, Jim Berry, was the head coach at Shadle Park when that school won the first Washington boys cross country title in 1959. That win starting a Spokane snowball that’s hardly abated in the nearly fifty years since. Mentored under Bob Barbero, yet another respected GSL coach, Berry has been readily accepted into what is widely regarded as a fraternity of competitors. “We all coach differently,” Mike Hadway of rival Ferris says, “but with the same basic roots.” Hadway, with 23 years at Ferris, is good-naturedly regarded as the dean of Spokane coaches now that Tyson has moved on. “The coaches all support each other,” he says. “And young guys like James Berry are brought into the fold. We cheer for each other’s kids....as long as we’re not racing them.” That caveat— as long as we’re not racing them—gets at the dichotomy within the fraternity. The teams of the Greater Spokane League want to see each other succeed on a state and national level, just not at their own expense. “There’s definitely the GSL pride,” Berry says. “A school from the GSL has won state for the last 19 years. If we can’t win it, then we want someone else from the GSL to win. But we want to win it.” Across town, the runners from North Central express a similar sentiment. They talk about how the success of programs like Mead and Ferris have inspired them, but also made them eager to prove their mettle and end the two-way dominance. “We’re always pulling for each other at state,” Leon Dean says, “but if we’re racing against each other—” "If we're racing each other," teammate Adam Reid finishes, “well then...it’s game on.”

Back on the Backporch  The ice cream bowls are scraped clean and long-since cleared by Leta. The sun has dropped behind the distant hills, reflecting a ragged orange treeline on Tracy Walters’ glasses. He scans the valley below, taking in the landscape, considering the hills, trying to pull more answers from the mid-sized American city that sprawls beneath. The ice cream bowls are scraped clean and long-since cleared by Leta. The sun has dropped behind the distant hills, reflecting a ragged orange treeline on Tracy Walters’ glasses. He scans the valley below, taking in the landscape, considering the hills, trying to pull more answers from the mid-sized American city that sprawls beneath.

“Have we covered everything?” he asks, nearly four hours after the visit began. It’s a rhetorical question; he’s providing his own answers. “I don’t know whether we’ve covered the entire ground. We’ve turned over the ground. We’ve exposed it.”

Then he laughs to himself and admits that it’s probably time to wrap things up anyway. The hour is getting late. It’s a tough drive back in the dark. But maybe just one more story about Gerry.

One more thought about the impact of Pat Tyson.

One more reason for the greatness of Spokane running.

One more reflection about love.

One more season to discuss.

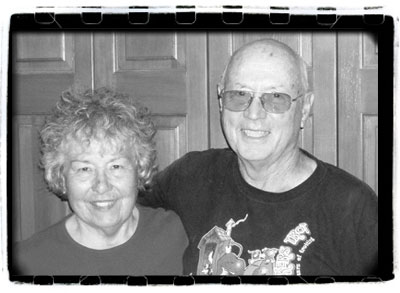

Leta and Tracy Walters at their home, Photo by Dave Devine

It is late summer, 2007. More than forty years since a skinny kid with a squeaky voice and an astonishing capacity for pain put this working class city on the map. That kid’s coach, nearly seventy-seven years-old now, looks out at the fading Spokane sky and smiles.

“How about these kids from North Central?” he says. “Man, are they gonna be good.” |